An Interview With Guy Lillian III - A Letter Column Contributor Made Good

/Written by Bryan Stroud

Guy H. Lillian III

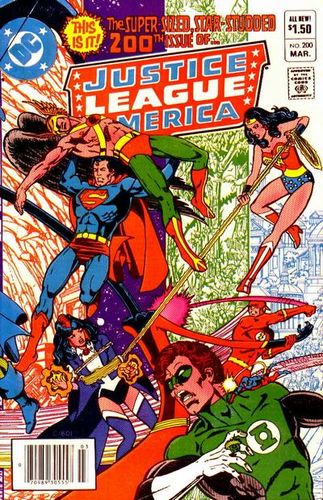

Guy H. Lillian III is a Louisiana lawyer, former letter column contributor, and science fiction fanzine publisher notable for having been twice nominated for a Hugo Award as Best Fan Writer and having had a row of 12 nominations (without winning) for the Hugo for Best Fanzine (for Challenger). He is the 1984 recipient of Southern fandom's Rebel Award.

Having studied English at Berkeley, writing at the UNC Greensboro, and law at Loyola University New Orleans, he practiced as a defense lawyer in the field of criminal law in Louisiana as his day job.

As a noted letter column contributor and fan of the comic book Green Lantern, Lillian's name was tributized for the title's 1968 debut character Guy Gardner.

A Guy Lillian letter published in the Flash-Grams letter column about Ross Andru & Mike Esposito taking over art duties with Flash #175.

One day it occurred to me that it would be interesting to try and track down some of the prolific lettercol contributors from back in the day - and better yet, those who had transitioned to the professional ranks in one form or another. E. Nelson Bridwell was probably the first fan-turned-pro, but there were others to follow. One of them, of course, was Julie Schwartz's "favorite Guy," the one and only Guy Lillian III, who had some wonderful memories to share.

This interview originally took place over the phone on January 13, 2010.

Bryan Stroud: Quite obviously you were a comic fan as a youngster. What prompted you to start writing in?

The Flash (1940) #133, cover by Carmine Infantino.

Guy Lillian III: I was 12 years old and I was at my grandmother’s house in a little town called Rosamond, California. It was there I first found a copy of The Flash in a stack of old magazines – and been hooked. I read in the letter column some of the things people were writing in. At the time Julie Schwartz was editing Flash, and had a contest going, where the people who sent in the cleverest letters won original artwork and scripts. They can’t do that now. So, what they would do was write unbelievably corny, pun-filled letters. And for some reason Schwartz responded to that, and awarded artwork to these terrible letters. That ticked me off, frankly, because here these guys are getting all these treasures and I didn’t have any of these things, so I got upset about it. I wrote – by hand, on a tiny lined pad (I still remember it) saying that these guys were lousy comedians and he should save his prizes for more worthy efforts. Then I forgot about it.

The next thing I know, I’m living in Riverside, California. I was about 13, I guess and I’m buying Flash #133. It featured the stupidest Flash cover of all time. It showed Flash as a wooden puppet running past a poster of Abra Kadabra, one of his villains, who was shooting a ray out at him. The thought balloon read: “I’ve got the strangest feeling I’m being turned into a puppet!” Ludicrous cover. Anyway, I looked in the letter column and I saw at the very end, I’ll never forget this, “And finally –Guy Lillian—despite himself—is stuck with the original script for ‘Kid Flash Meets the Elongated Man’.” I couldn’t believe my eyes. I leafed through the letter column and found my letter. I raced home, ecstatic. I just couldn’t believe it. Sure enough, they sent me the script. “Kid Flash Meets the Elongated Man”, which was a John Broome script. The script was fascinating. I saw the way scripts were put together over at DC and I really enjoyed it. So I kept writing letters of comment, and Julie kept publishing me, and the rest is history.

Stroud: Do you still have the script?

Phantom Stranger (1969) #34, featuring “A Death In The Family!” written by Guy Lillian & Arnold Drake.

GL III: Yeah, someplace. I don’t know exactly where. I was a little disappointed that I didn’t get artwork because that would have been much cooler, but I eventually did get some: a Hawkman issue. I had to sell it eventually, because I was so broke. But the years when I was Julie’s “Favorite Guy” were an amazing time.

Stroud: As you got acquainted with Julie, what were your impressions of someone I presume was one of your heroes at the time?

GL III: I’ve got two stories to tell about that. The first one took place in 1966, a few years later. I’d become friends with Mike Friedrich, who was a fellow comic letter hack. I was in high school and Mike, who lived in Castro Valley, California, organized a little comic book convention for local comic book fans. Most of these guys were a couple of years older than me and were involved in things like CAPA ALPHA, a comic book amateur press association. It was a lot of fun; we talked with cartoonists from the local newspaper who came by and watched the Republic Captain America serial, but here’s the thing: Julie Schwartz was visiting San Francisco, which is across San Francisco Bay from where we lived. Very close. And he said, “Why don’t you guys come and see me at my hotel?” And we were all excited because a Mike and I and a couple of other guys were going to see Julie Schwartz.

Mike wanted to write for comics and had written a script to show Julie, a pretty terrible, amateurish job. (Of course, he eventually ended up being a comic book writer.) Of course, partway to San Francisco he realized he’d forgotten the script, so we had to go back to get it. On the way back a woman, who was getting groceries and apparently not busting with intelligence T-boned us. It was a complete disaster. The other two guys and I ended up in the hospital. I had a hematoma in my leg and was laid up for days. I felt worse for Mike, because while we could sit around in the emergency room and cheer each other up, he had to go home and sit in his little room. He had to call Julie and tell him we couldn’t make it, so he was very alone and depressed, whereas I and the other two guys were just celebrating the fact that we were still alive in the hospital. That was July 9, 1966. I’ll never forget it.

Challenger (1993) #17, cover by Paul McCall. Edited by Guy Lillian.

I finally did get to New York in 1972. I was in graduate school at the University of North Carolina, getting my Master of Fine Arts. A long time had passed. Six years. I decided to jump on the bus to New York City. Of course, I had to go by DC Comics. I called Julie and asked if it was okay if I drop by. He said, “Sure,” and so I did. I went up there and met the man. I met him and I met Sol Harrison, the one who would eventually become my boss; Carmine Infantino came in and Elliot Maggin. Great guy. I think Cary Bates may have been there. I had a fine time just yakking away and wandering around and just having a great day. So, while I was in North Carolina getting my Master’s I became friends with a lot of the young staffers like Paul Levitz and Carl Gafford and some of the Marvel guys like Tony Isabella.

Some of those cats and I joined CAPA ALPHA. I was already involved in science fiction fanzines – the mighty Southern Fandom Press Alliance – so I joined CAPA ALPHA, doing fanzines about comics. I was already known for my letters to Julie; he’d published about a hundred. I had 120 published all total. So I just started hanging out at DC. Then one day Paul Levitz calls me up and says, “Look, how would you like a job?” “Sure.” So, after I graduated with my Master’s degree I got a job at DC Comics at the magnificent salary of $100.00 a week to start, which was later raised to an even more magnificent sum, $110.00 a week. In New York City. It was paradise. It was terrific. I had a great time.

Stroud: I can just imagine. It had to be surreal at the beginning.

GL III: It was weird. I used to come up to DC Comics all the time while I was in North Carolina and they got used to seeing me around. As a matter of fact, once or twice, I think, I just sat down in a little room there and wrote up a letter of comment and they published it. Later on, after I started work, we began The Amazing World of DC Comics, a fan-oriented magazine. It was basically a response to FOOM (Friends Of Ol’ Marvel) which was much, much less sophisticated than Amazing World. I had some ace assignments.

Amazing World of DC Comics (1974) #3, cover by Joe Kubert.

I went over to Joe Kubert’s house and interviewed him. I did an interview with Maggin and Bates, which was lots of fun. I did an interview with Mort Weisinger, the Superman editor at one time. The big thing I did was write a biography of Julie Schwartz for Amazing World #3. I got Kubert to do a portrait of Julie for the cover. Among other people – this is amazing – I interviewed Alfred Bester at his home on Madison Avenue. He was a phenomenal conversationalist. I have never met anybody like that. One of the greatest conversations in my life. When I read the article I eventually wrote nowadays, it seems amateurish and “gosh, wow”, but Bester liked it. He called Julie and paid me an enormous compliment. He said, “If I were still at Holiday magazine, I’d hire that guy.”

I worked at DC comics for a year and then I got itchy. I was in love with a girl in New Orleans, so I wanted to move back there. I’d lived in New Orleans before. New Orleans is the type of town that gets its hooks into you. You never get over it. So I wanted to go back there, which was stupid but as it happens all the young staff got fired and then rehired a couple of months after I left, when DC Comics went through an upheaval. Carmine got fired as publisher and everything went topsy-turvy. I don’t know if I’d have been able to survive. Certainly not with the salary I made. Also, I was living in East Harlem in a high rise, so I’d lean out my window at night and watch knife fights. I am not kidding.

Stroud: Oh, no.

GL III: Yeah, it was just horrible. So, I wanted to go home to New Orleans. It was stupid and immature and I wish I hadn’t done it, but that’s the way the corn flakes. Life took me in a different direction. I kept in touch with these guys and I still kind of keep tabs. But no regrets about my DC experience; it was a life-altering and a life-enriching experience. I met some incredible people. I got to watch some of the most creative commercial guys in the world. Julie Schwartz, number one, of course. Hell’s bells, when I wrote that article about him, Ray Bradbury sent me a little note that I printed. Ray hasn’t done much recently, but at the time he was Valhalla. And he wrote me a letter! And of course, I knew Kubert and I knew [Bob] Kanigher, who was a wild man, but I really loved his work and him, too. I can’t pass up Sol Harrison. He was very generous to me. All of these people – it was just an incredible experience. An incredible year and a great way to spend part of one’s youth.

Guy H. Lillian III, ca.1971

Stroud: It just had to be beyond belief. Did you get to work much with Jack Adler?

GL III: Jack Adler was the production manager, wasn’t he?

Stroud: Yes, and ultimately Vice President.

GL III: Yeah, Jack and Sol had known each other since they were young and it was really a riot to talk to them. At that point in time he was at his best, training cats like Steve Mitchell and Bob Rozakis, who later took over his job. Jack loved to pass long old Jewish sayings and explain them because we didn’t know any of that stuff from the old neighborhood. He was a really funny man and I liked him a great deal.

Who else did I know there? Kurt Schaffenberger was one of the artists, as you know. He was the guy who did a lot of Lois Lane and he was just a terrific artist. And Curt Swan. Man, this guy never got the credit he deserved. He wasn’t young. He wasn’t fancy. But he was very workman-like and could really hold a story together. And he could draw. He was just great. Murphy Anderson was a nice guy. I only met him once. A very, very good artist. These guys were real pros. They were just outstanding.

I met Neal Adams. Neal was flighty, but he was an incredible talent. He had problems with deadlines. A lot of them did. Mike Kaluta had terrible problems with them, but he was a terrific artist. These were great guys, but they just couldn’t understand that you had to get the work finished and to the printer on time. It was a generational difference that was really striking there. Joe Orlando, too. He was a nice man. Another great artist, of course.

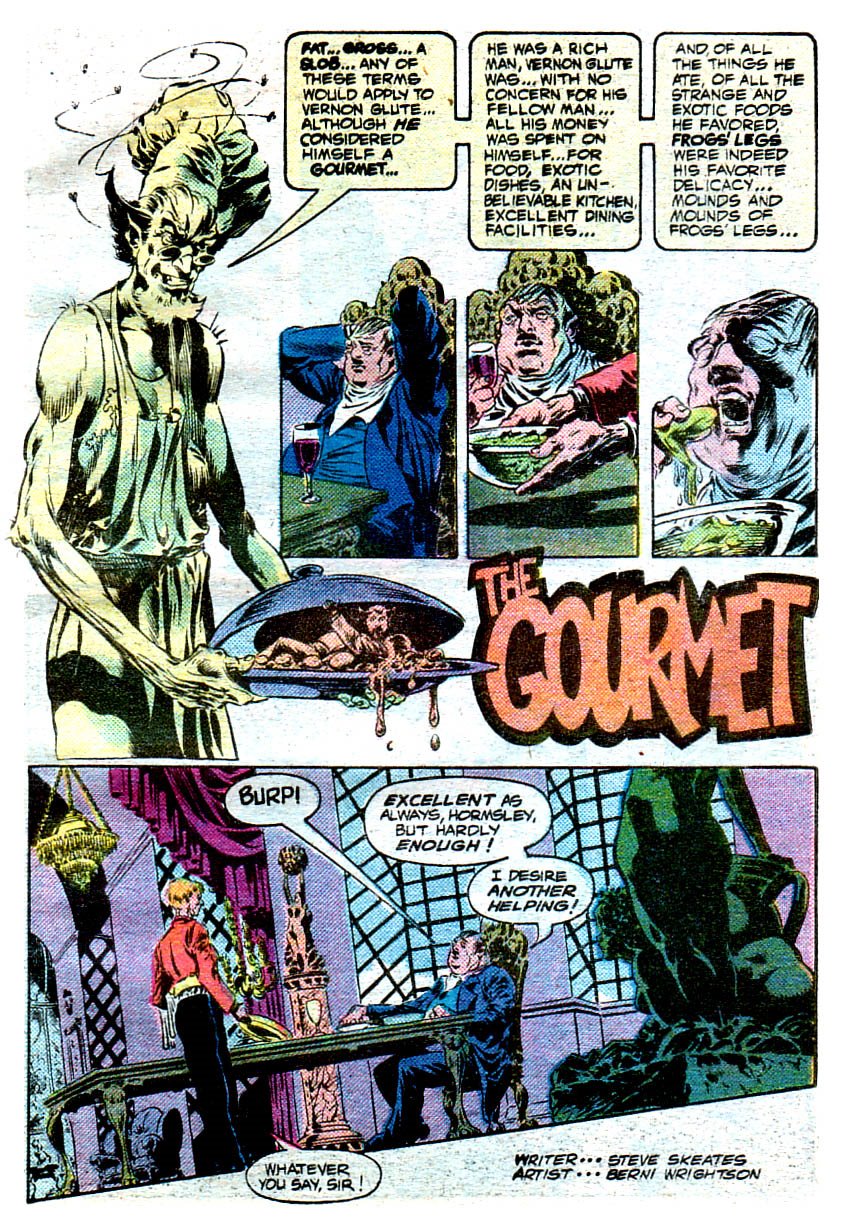

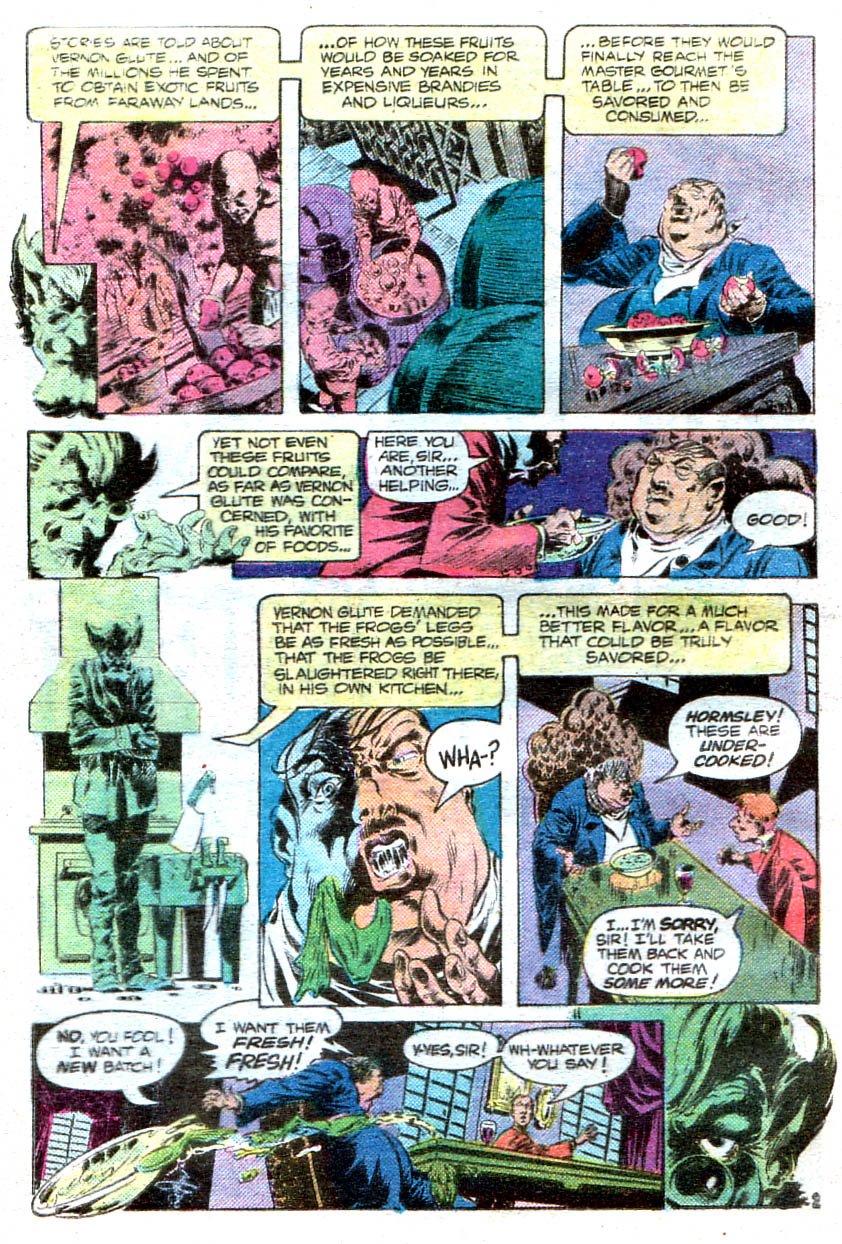

Secrets of Haunted House (1975) #5, featuring “Gunslinger!” written by Guy Lillian.

Stroud: One of the best. It’s amazing the contributions he made to the genre both as an artist and an editor.

GL III: He gave me the job that was probably the one I enjoyed the most: re-writing dialogue for unused stories that he had on file. He had the finished artwork, but he didn’t like the way the stories were told. The writing was stodgy. He gave me a chance and said, “Why don’t you try to write the dialogue for these?” I wrote about six. They were all published. I really enjoyed doing that.

Stroud: There’s a rumor that there’s a DC character named in your honor. Any truth to that?

GL III: I always thought that. The DC character was one of the alternate Green Lanterns named Guy Gardner. I always suspected that he was named after me and Gardner Fox, but I couldn’t tell you for sure. Nobody ever said yea or nay.

Stroud: The common wisdom is that Fox was honored with that one and Gardner Grayle of the Atomic Knights.

GL III: (Laughter.) One of the big disappointments in my comics fan history came when Julie was taken off DC’s science fiction titles: Mystery in Space and Strange Adventures. Strange Adventures had three great series; The Atomic Knights, Star Hawkins and Space Museum, which I really liked. Because that was the one place where he allowed Carmine Infantino to ink his own pencils. Carmine loved to do that, and his inks were very expressive, but a little bit raggedy. I liked the way he did it. But Julie didn’t like it, so he just kept it in Space Museum. He didn’t let him do it on the other two things he did, Adam Strange and of course Flash. I really liked those science fiction books and it was a shame when he lost them. But they gave him Batman, so you can’t knock that.

Stroud: Yeah, and he brought it back from the brink by all accounts.

A Guy Lillian letter published in Detective Comics (1937) #375 - continued below.

GL III: Julie always gave himself a lot of credit for that. I think he deserved more credit for saving Superman than he did for saving Batman. When he took over Batman it made a great deal of difference, I think, but I believe the guy who really saved Batman was Frank Miller. But that’s speaking as a fan and not as a friend of Julie’s. And Julie became a very good friend. After he retired from editing, and became a roving ambassador of good will for DC, I’d see him all the time at science fiction conventions. We’d hang together. He was just a wonderful cat. We just had a great time together. I used to say “Would you like to see my Julie Schwartz imitation?” and doff my hat and show everyone my bald head. He was an amazing man. Very funny. Very warm. A very kind gentleman.

If you ever read my article in Amazing World about him, it looks a little bit hurried to me now, but he liked it. He was very proud of it; he sent copies to a bunch of his friends. I was very, very pleased with that. He was the first adult ever to pay attention to what I had to say. All through my adolescence he was there, a great, great influence on me. He called me “his favorite Guy,” which I thought was very corny, but what the hell, it was a compliment – one of the best I’ve ever had.

Stroud: (Laughter.) You were a man of letters at that time and yet you went into something considered rather lowbrow at the time. Did you give that any second thoughts?

GL III: Not at all. A job was a job was a job and I always have respected the genres. When I was in college I invited myself up to see Poul Anderson. Instead of having me shot like he should have he was generous and got me involved in science fiction fandom. I’ve never looked back. My wife Rosy and I have gotten to go to Australia through science fiction fandom. I’ve had 12 Hugo nominations, including ten for my magazine, Challenger, which I’m very proud of.

A Guy Lillian letter published in Detective Comics (1937) #375 - continued from above.

I regard myself as a science fiction fan more than a comics fan these days, and I prefer science fiction fandom to its comics cousin. I’ve been to comic cons. I used to go to Seuling cons in New York City in my youth and they were okay, but comic conventions are a little young for me now. They’re also very commercial, so I kind of stay away and avoid them.

Stroud: I’ve never been to one, but it sounds like the comics are beginning to get shunted aside in favor of movies and television and video games and such.

GL III: That’s true. The mark of our success in science fiction is that the movies took over. That typically means that SF was good, and what does good mean in the commercial sense? Movies and the enduring popularity. People recognize your quality; they know who you are and who the characters are. People know who Superman is. People know who Spider-Man is. My wife works in the communication department at the university in Shreveport and they had a class in comic book movies. Movies taken from the comics. So, it’s there. It’s the mark of our success that our own genres have gotten away from us.

Stroud: My best friend and I recently attended the Faster Than a Speeding Bullet art display of original comic work at the University of Oregon and it covered work through all the decades and I couldn’t help but think things have come a long way from when they were trying to ban all this in the 40’s and 50’s.

GL III: Well, what they were trying to ban in the 50’s was the EC horror stuff more than anything else. Everything in comics got tarred with the same brush, which was unfortunate. But some of that horror stuff was kind of gross. But that was a different breed of cat from the superhero comics. Their appeal was to a slightly older, slightly more sophisticated audience. It was like the competition between Marvel and DC. I didn’t really see it as a true competition because Marvel appealed to a little bit older audience than DC. DC Comics was for tweeneers -- kids in early teen years. Marvel appealed to kids who were in their mid-teens and so on. I didn’t see any problem with that. I always enjoyed everyone’s stuff. I couldn’t stand the competition in a lot of ways, because frankly some of their people got kind of obnoxious, but I’m sure they said the same thing about me.

Unexpected (1968) #201, featuring “Do Unto Others!” written by Guy Lillian & Mary Skrenes.

One thing I remember is when I went and interviewed Bob Kane. I never saw a better collection of comic book art than he had on his wall. Prince Valiant originals – man! But the poor guy, everything in his life was dominated by Batman. The soap in his bathroom was those little squirt dispensers of bat-soap and it was decorated with Batman wallpaper because he got it all for free. He didn’t let me print the interview I did with him because he thought it would interfere with his autobiography.

(“Batman and Me,” which sits on my bookshelf was published in 1989.)

Stroud: There are some pretty notorious stories about Mort Weisinger. How did you find him?

GL III: I enjoyed my interview with Mort. It was the last interview I did for Amazing World. One thing he liked to do was show people the checks he got for some of his other writing. I got the feeling he always resented his association with Superman, where he was the editor for so many years. Everybody tried to tell him, “Look, this is an absolutely great thing to be a part of. This is American folklore. Ask people the world over, if they’ve heard of your novel about beauty pageants and no one will say so. But have they heard of Superman? Of course! There isn’t a human being on this planet that hasn’t heard of Superman!”

Another thing I can say about Mort is that he and Julie enjoyed a lifetime of friendship. It was quite fun to listen to Julie talk about Mort and the other guys that he knew back in the day – because he knew everybody. I mean the man knew Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft and Howard corresponded, but they didn’t meet, but Julie met both of them. It was fun to talk to Julie about his early days in science fiction fandom because he helped found it. He was the first guy to do a science fiction fanzine. I think of myself as being in his lineage.

Stroud: I’d say so, especially since you’re still keeping up with it after all this time.

GL III: My genzine, Challenger (www.challzine.net), has gotten me a lot of recognition and as I already mentioned my wife and I got a wonderful trip to Australia. An incredible experience. It gets us to the best parties in the world science fiction community, too.

Challenger (1993) #19, cover by Ned Dameron. Edited by Guy Lillian.

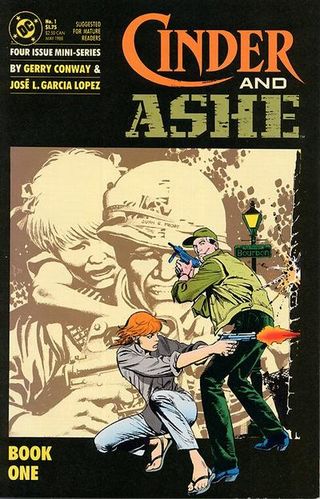

Stroud: Not bad at all. Did you ever do any writing for the comics?

GL III: No. When I went down to New Orleans I didn’t give up reading comics, but I did give up writing letters. Frankly, I’d said what I had to say. I wrote a couple afterwards – one to The ‘Nam is memorable – but I gave it up as a hobby.

As to writing comics stories, that’s not really what I ever wanted to do. When I got back to New Orleans I pursued another old interest and went to law school. I’m only a public defender, which is at the bottom of the heap according to a lot of lawyers, but I love doing it; it’s very rewarding emotionally. The stories you hear are just fantastic.

The real world has its distractions. Some are horrid. I interviewed one of the Manson girls once and I’ve known some people I wouldn’t let my wife in the same time zone with, but appearing in court, arguing for people, doing trials, that is very rewarding, entertaining, and enlightening. You learn an awful lot about human nature.

Have I given up writing altogether? No, I’ve still got some ambitions. It would require an awful lot of work because I think my writing is a little stodgy, but nevertheless I still write articles for myself for my amateur magazine. I like to write about the people that I’ve known and the things that I’ve seen and some of the events that I’ve attended. It’s been a fascinating life and I want to preserve some of that.

A small gallery of Challenger fanzine covers

Challenger (1993) #20, cover by Frank Wu. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #21, cover by J.K. Potter. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #22, cover by John Dell. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #24, cover by Brad Foster. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #28, cover by Sheryl Birkhead. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #30, cover by Frank Kelly. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #37, cover by Ron Sanders. Edited by Guy Lillian.

Challenger (1993) #41, cover by ?. Edited by Guy Lillian.