An Interview With Mike Esposito - Silver Age Inker for Wonder Woman & Iron Man

/Written by Bryan Stroud

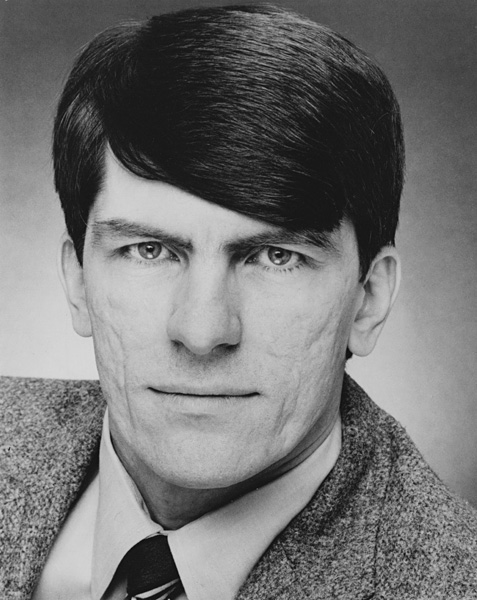

Mike Esposito at his desk.

Mike Esposito (born July 14, 1927) was an American comic book artist - who sometimes used the pseudonyms Mickey Demeo, Mickey Dee, Michael Dee, and Joe Gaudioso - whose work for DC Comics, Marvel Comics and other publishers spanned from the 1950's to the 2000's. As a comic book inker teamed with his childhood friend Ross Andru, he drew for such major titles as The Amazing Spider-Man and Wonder Woman. In 2006, an Andru-Esposito drawing of Wonder Woman graced the front of an American postage stamp.

Esposito was inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame in 2007. He passed away on October 24, 2010 at the age of 83.

Mike was a treasure and kept me in stitches for the entire interview. A sharp wit coupled with some wonderful stories made this conversation a complete pleasure. I was proud that Mike and I struck up a long-distance friendship and we had many an enjoyable call afterward until the sad day that his wife, Irene gave me a call. "I just spoke with John Romita and Stan Goldberg and now I wanted to let you know that Mike has passed away, but your calls meant a lot to him." Well, Mike meant a lot to me, and I still miss him.

This interview originally took place over the phone on July 25 & 28, 2008.

Wonder Woman (1942) #98, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Bryan D. Stroud: I wanted to start by wishing you a belated happy birthday. I missed it.

Mike Esposito: That’s okay. It’s a good thing you did. How many more could I have? 81, my God.

Stroud: Well, hopefully several more. (Chuckle.)

ME: You never know. If I owe enough money, I should last longer.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: Gotcha.

Stroud: Who do you feel was your biggest artistic influence?

ME: When I was a kid?

Stroud: Yes.

ME: Milton Caniff. Terry and the Pirates. It was very good stuff. A little simplistic. Not the way they draw it today. I guess John Romita was also influenced by him. His stuff had that look. Johnny Romita with his Spider-Man stuff like that. You’ll see that softness, that clean brush line.

A few guys over the years imitated him and spun off their thoughts from him and their technique. But I would say Milton Caniff and naturally Walt Disney, because I wanted to be an animator. Ross [Andru] and I were supposed to go to Disney when we were 17, but my father said, “No, I’m not letting you leave to go to California.” I was 17, so I said, “Please, please, please,” and what happened? I got drafted and went to Germany.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: There you go. The best laid plans of your daddy.

Stroud: Funny how things work out. Rather than halfway across the country, you’re halfway across the world.

ME: Who knows what I would have been up to at Disney? Because I had some great artistic thoughts. When I wrote “Get Lost;” - Ross and I - that “Get Lost” book, you ought to get a hold of. It’s very funny.

Stroud: Yeah, I’m looking forward to that. I see it’s available on line.

ME: Amazon should have it. I think they discount it, too. It’s two bucks less.

Stroud: I saw what you were telling me, too. The cover on it does look like what you’d see on a Mad magazine back in the day.

Get Lost (1954) #1, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

ME: Oh, that’s why they sued me. You see at that time Mad was a comic book and not a magazine yet, and his editors felt that we were swiping because we had the same distributor. Leader News. And they thought they were giving us the money to put out the book and they didn’t do any of that. We did it on our own and we went a different way than them. We went into lampooning movies, which they didn’t do. They lampooned everything.

And we made fun of them in a couple of stories and that bothered them. For instance, if you ever saw the book there was the sewer keeper, which we took from the Crypt Keeper. We called the guy “Sickly.” The original concept was a weird name like that, so we made it “Sickly.” Everybody was insulted. So, I went to see Gaines and I said we wanted work. We pulled our horns in and left the business and we wanted to go back into freelancing. Feldstein came out and he said, “You’re the last people in the world we’d give work to.”

Stroud: Oh, no.

ME: Because we screwed them, he said. He said we copied them. And they lost the lawsuit. It was thrown right out of court. The judge said, “You can’t copyright humor.” And that was it.

Stroud: Well, that was at least a sensible judgment.

ME: Well, he was right. He was laughing all through it when he was reading the book. He was laughing. It was a funny book. I have to admit. (Chuckle.) When I looked at it recently when I got copies from my publisher, I said, “Gee, I didn’t realize I did this.” I was only 23. You know you’ve got a vibrant brain.

Stroud: Sure, your imagination going all over the place.

ME: Oh, my God. Ross and I would be up until 5:00 in the morning. We’d work around the clock. And he had a dry sense of humor. I was more zany. I was more off the wall. Slapstick. And Ross was more clever, deep, dry humor. The combination was great because his dialogue in those balloons were very good and I was more silly. More Jackie Gleason. And we really hit it off.

Stroud: You shared the writing on it, then?

ME: Well, later on we did a book called, “Up Your Nose and Out Your Ear.” I don’t know if you ever heard of it.

Stroud: Yeah, I think I did.

ME: Well, we did that because we wanted to do a dissenter’s book. Dissension. We were teed off at the world, and politics, and racial prejudice; everything that was bothering us as liberals. We were irritated, and we wanted to make a book about it. We put out a book called “Up Your Nose,” and the reason why the title was what it was…my wife hated the title. She wanted to make it “Get Lost 2,” like an extension of “Get Lost.” But Ross felt that because with “Get Lost” we were getting sued and everything, he didn’t want any part of it. So, I said, “Okay.” Johnny Carson used to have an expression on T.V.: “May the bird of paradise fly up your nose, and out your ear.” So, I said, “Hey. Why not? ‘Up Your Nose and Out Your Ear.’” “It’s not bad,” Ross said, “Why not?”

So, we had t-shirts with the finger going up your nose. We sold a lot of t-shirts. The college kids loved it. Because it was the deep, dry humor that made sense. And there was one character I created with Ross called Thelma of the Apes, and she was naked…all the time, in the jungle. She was like Tarzan. She comes to America and actually she gets turned on when everybody is fighting her, but when anybody is fighting she goes back to her gorilla mentality of the jungles, and she joins the fights. She gets in a lot of trouble. It’s called “Thelma of the Apes.” And also, there’s this bit where a bunch of lesbians come out in a parade and they start a fight with her (chuckle), and…I can’t explain it, but it’s funny when you look at it.

Up Your Nose (1972) #1, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: It sounds terrific.

ME: Well, the college kids loved it, because they saw what we were doing. We had the mayor, with all the screw ups, Mayor Lindsey at that time, and we did two issues. We were starting our third one with Marlon Brando, a take off on Marlon Brando, and we were knocked out of the box because what happened was the distributor said, “We got a winner!” He got so excited; Kable News, he called us up and said, “We’re going to bury Mad Magazine!” Because he approached it as a magazine, not a comic book, like Mad, and he said, “We got a winner!” Then all of a sudden, the books started coming in from Hawaii, from the west coast. Carloads. Because they thought it was a drug book. And it wasn’t! But when they heard “Up Your Nose;” cocaine.

And also, the main character was Joe Snow. And that was his name! My daughter knew him from school. So, he was perfect for the book, and we gave him a contract, and he appears in all the stories in photographs and we’d draw around him. It’s kind of cute when you look at it if you ever get a hold of one. They’ve got to be in second hand bookstores and so on. Definitely I want you to see “Get Lost.” Because that one, we put our souls into that. You’ll see the artwork in that, for that period, 1953; nobody drew that way. There was so much detail. I’m talking about certain stories, not all the stories, because we didn’t do all of them. We did the lead stories and so on, but they were good. And the caricature of John Wayne in the Hondo type movie…you’ll like it.

Stroud: Great. I look forward to getting a copy.

ME: You should. You really should. As a fan of Mike Esposito, you should.

Stroud: (Chuckle.) Absolutely. What sort of art training did you have, Mr. Esposito?

ME: Call me Mike, please.

Stroud: Okay, thank you.

ME: I went to the High School of Music and Art. Ross went there. Joe Kubert went there. Lots of guys that finished up. Frank Giacoia. We all went there. Well, some of them went to Art and Design, which was right nearby. Mine was in Harlem. It was created by Mayor LaGuardia for underprivileged kids who were artistically gifted in music and art. In fact, Bess Myerson, the famous Miss America went there. Some great musicians went there. Kids that became great artists went there. And it was a good school.

Stroud: A very impressive alumni at the very minimum.

ME: Oh, yeah. There were some great guys who came out of there. Joe Kubert came out of there…wait. I’m wrong. He and Frank Giacoia and Tony Bennett came out of the High School of Art and Design. Which was very similar to Music and Art. But it was right there in New York while we went to Harlem.

Rip Hunter Time Master (1961) #1, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: So that was how you and Ross got acquainted?

ME: Well, we got acquainted in class through a girl from France. The war was on, and this little French immigrant girl who could barely speak English, but she was so sweet, and she saw me do a sketch on the wall, on the blackboard, of animation; how it’s done. I was about fourteen and a half, and I was showing how it was done. How you make the in-between animation and extreme animation. And she was so impressed. She got me up to the class and she said, “There’s somebody I think you should meet. He’s a very shy guy from Cleveland.

He was born in Cleveland, and he moved to New York, and he skipped the first term. I’ll have him meet you.” So, I said, “Meet me down by the tree.” Off the side of the school building there was a big tree. So, he met me there and he was making snowballs. He was very clumsy (chuckle), poor guy. It was like he had two left feet. He could never play ball. I could, but he had no rhythm. In fact, my son, who passed away, was just like him. Maybe he’s the father. (Chuckle.) He was so similar and disoriented. They both had two left feet.

Stroud: No coordination, huh?

ME: That’s the word. Coordination. Both were brilliant. My son, of course got it from me, really.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: I’m kidding. But Ross would show me his drawings, and they were so crude, I said, “Boy, this poor kid. He’s not gonna make it.” They were heavy handed and crude and it was supposed to be a cartoon; very simplistic. But it wasn’t. But he was going another way. He was seeing it in a different perspective. He was seeing it as art rather than simplistic cartoons, so he loaded it up with detail. But it didn’t look Terry Toons. It didn’t look like the simplistic animation of the old days. And so, I said to myself, “This kid’s not gonna make it.” I felt bad for him. What happened was I started explaining to him what was wrong. And he exploded, and exploded, and exploded. He passed me like a bullet. And I grabbed his coattails and zoomed with him. “Go ahead, Ross. I’m your partner for life.”

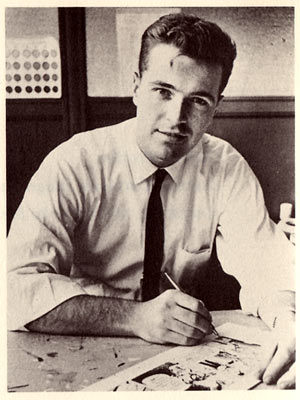

Ross Andru & Mike Esposito, partners for life. (1977)

But anyway, that’s when we became partners. We shook hands and said, “Partners for life.” No contract. Of course, we separated from time to time because of the business being the way it is. He went his way to DC at one point and I stayed with Marvel. Then we came together again after his wife passed away and we were going to publish together. We had these brokers all hot and heavy to do the work, and they screwed us. Wall Street can be very, very bad with all the promises. Well, look at Wall Street today. It’s just as bad.

Stroud: Oh, yeah. There’s no heart there.

ME: Not only that, the dreams can explode so quickly. We were promised so much stock and they were all liars. It was whatever they could get out of it. And we’re going ahead and we’ve got plans upon plans and we’ve got writers. I almost had a nervous breakdown over it. I just felt so responsible for all the people who were lining up. And then I had to tell them, “It’s over.” Did you ever see the movie “Pal Joey?” With Frank Sinatra?

Stroud: Yes.

ME: Remember when he had to go back to the nightclub and say, “It’s all over?” They pulled out on him. Rita Hayworth. She took the money and she said, “We’re going to close Café Capri,” or whatever it was. And he had to tell all the help. They couldn’t believe it. Well, that’s what happened to me, in a sense. I had to tell all the people that were so excited about this venture, “It’s no more.” Almost overnight. It’s not easy. Not easy being me.

Stroud: Do you feel that when you spent time in the service that it was helpful later when you were doing the war books for DC?

ME: No, it didn’t help me that way. It helped me get to the idea that I wanted to be a cartoonist.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: I really mean it. I couldn’t wait to get home.

Mike Esposito, soldier/artist.

Stroud: (Chuckle.) Soldiering was not your thing, huh?

ME: It was not. One thing was good about it. It says in my book with Ross in the history, “Andru and Esposito, Partners for Life,” in there it says I caught myself saying, “One thing about the Army: I never was frightened about falling down or being left alone.” I always had a problem psychologically all my life, as a young fella, with anxiety. Always had it, and if I was on the subway too long I’d get a little panicky and crowds would bother me. Of course, I got over it as the years passed, but at that time I was 17 and it was pretty rough.

So, when I was in the Army, I had no fear of that. And the reason why I say it in the book was that the Army was my mommy and daddy. If I fell down, they picked me up and took me to the hospital. I’m Government Issue. I’m their property, and they will take care of me. So, I felt confident. I wasn’t alone. And maybe I’m stupid to say that, but I have to be honest with you, that’s exactly the way I felt.

So, when I came home, I couldn’t wait to get into the artwork business, you know, comics. So, Ross and I went to a school. We went to Burne Hogarth’s Cartoonist’s and Illustrator’s School. That’s where Jack Abel was, that’s where Joe Kubert was. Joe and I were very close. We were both up at DC. I couldn’t believe it. He started in comics in his early teens, and I’d just come out of the Army. And Ross and I heard about the school, which he had gone to also. Burne Hogarth was very much a guy who was into himself. When he’d get up to teach us, we were all in awe of him, but he wasn’t really teaching us. He was telling us his life. There are two ways to teach: You teach, and we absorb; you B.S. and we just look at you and say, “Very entertaining.” But nothing happens. You get the drift?

Stroud: (Laughter.) I sure do. I’ve had instructors like that.

ME: There you go.

Stroud: Very impressed with themselves.

ME: Right. He was good, though. He was impressed with himself, but he was also good. He could cut the mustard as well as spread it. And the point is that he picked Ross right out. When he was working on Tarzan, the syndicated strip for the Sunday page, he wanted to do other things, Burne Hogarth, and he said, “I need an assistant, so I’ll get one of my students real cheap.” Because he’d give them $25.00 a week for each page and the Government would pay another $75.00 through the G.I. Bill. On the job training, they called it. So, he grabbed Ross and taught Ross everything. And boy, Ross just ate it up. I’m telling you, Ross just studied by using big pages, doing just ears, ears, noses, noses, everything he could get from Burne Hogarth. Rocks, rocks, rocks, trees, tress, jungles, jungles, branches… I could never do that. I wouldn’t have the patience.

Captain Storm (1964) #13, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: It would drive you crazy after awhile I’d think.

ME: He did so many pages of that, that one day in our studio when we were doing pretty well in 1952 or ’53, Gil Kane came in. You know of Gil Kane, of course.

Stroud: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

ME: Brilliant, brilliant artist. A genius in his own right. He really was, for what he did. Of course, he was slow and he was not personable, but he was a good, good artist. And he came in and he saw these pages where Ross did all these sketches to improve his knowledge of all the noses and the ears as I said, and he said, “I would love to have that.” So, Ross said, “Well, they’re just sketches I made when I learned from Burne Hogarth.” He said, “I’ll pay you for them.” He paid him $100.00 for each page, which was a lot of money in 1952.

Stroud: Oh, absolutely.

ME: I didn’t get it, Ross got it because it was his stuff, and he took them and he studied them and then he met Burne Hogarth and became very close friends; Gil Kane with Burne Hogarth. For years they were like buddy, buddy, buddy. I saw Burne Hogarth at a convention for Marvel comics in 1977 and I walked up to him, and Gil Kane was there. I said, “Burne, you have no idea how appreciative I am of what you did for me.” He looked at me and with a twinkle in his eye he said, “What?” I said, “If it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t be here now. You taught me well, and I’m a professional now because of you. And my life is completely changed, and it’s everything I wanted to do.”

And he was in tears that I would say something to him like that, because guys are sometimes funny. They hold grudges. They’re mad at a guy for a reason and they never let go. Like the editor, Bob Kanigher. He made enemies, but I could feel sorry for him, because when he was sick, I put my arm around him and I felt sorry. And Ross said, “What the hell are you doing? He screwed us. He’s always screwing us.” I said, “Ross, the man is miserable right now.” I couldn’t help it. You can’t hate forever.

Stroud: No, no. Because it only hurts you.

ME: That’s exactly right.

Stroud: Good for you. I’ve heard a few horror stories about Kanigher.

ME: Believe me, they’re true. But he treated me well in one respect, and I told him this before he died. He wrote a letter back, in fact it was in a magazine with an interview with him and he said, “Gee, Mike, I wish my wife and family could hear that.” Because I said so many nice things about him. I said that he did what he did to me to make me a better guy, artist wise. He picked on me, tore me apart, (chuckle) but the things that hurt was I’d be in the taxicab downstairs with the pages to bring up, and I was listening to the Yankees ballgame when it was a no hitter. I’ll never forget it. I’m listening to the last pitch of the no hitter and I come running up the steps. It’s a little after 5:00 and he says, “Where the hell have you been?” I said, “I was downstairs listening to this ballgame…” “Ballgame?”

That was the furthest thing from his mind. He had no feeling for that. I said, “I’ve got the pages.” He said, “It’s too late.” “But I’ve got the pages.” And that’s what he would do. He would insult me. One time Ross and I (chuckle), well; maybe we were the Bobsey Twins. But the point is, we didn’t do it intentionally. We went into a store. Howard’s Clothing Store, one of the cheaper places, and we saw these very stylish for the time salt and pepper jackets with black pants. It was the wave of fashion in 1955 or 1956. So, we each bought a salt and pepper jacket with black slacks. We walk in (chuckle) to Bob Kanigher’s office, and he says, “Oh, the Bobsey Twins!”

Brave and the Bold (1955) #25, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: He made fun of us! But we looked good! We looked really good. All we needed was horn-rimmed glasses, sunglasses, and it would have been perfect. Like Will Smith would say, “But I look good!”

Stroud: (Chuckle.) Men in Black.

ME: Right. “But I look good.” So that’s the way Ross and I were.

Stroud: Great fun.

ME: Well, we had a lot of fun together. And we had our moments of irritation because he thinks one way and I think the other way and we fight back and forth until 3:00 or 4:00 in the morning, until finally we both agree. And we usually agreed, in the end. Of course, I was standing over him with a knife and shovel.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: He wasn’t a fighter. Neither was I. I’m kidding. I have to kid around, because if I don’t kid around, I die. I manage to keep going. Like the song keeps going on. The humor keeps going on. The day I can’t be funny, hey, it’s over.

Stroud: That’s right. What’s the point? In fact, it’s funny, I was going to mention to you it seems like throughout your career quite often you’ve been involved in humor related material.

ME: Oh, yeah.

Stroud: Do you remember when you and [Mike] Sekowsky worked on the Inferior Five, for example?

ME: Yes. I loved that book.

Stroud: You got a unique opportunity there to draw not only yourself but the other DC staffers in that one issue.

ME: Right, right.

Stroud: Was that quite a bit of fun?

ME: Oh, I loved it. In fact, in “Get Lost” there’s a page, the central page, the two-page filler they always had in those days, put in by law by the U.S. Post Office in those days in order to get the mailing cheap, and I drew Ross’ face smoking a million cigarettes and I drew myself with a puffy face, you know, a chubby face. At that time, I was blowing up my face by eating so many steak dinners and working around the clock. I got fat.

Stroud: Yeah, it’s hard to get any exercise with that schedule.

ME: We never did. Although we did run down the street on Broadway while the steam was coming out of the sewers at 4 o’clock in the morning just to work off the liquor.

Adventure Comics (1938) #374, cover penciled by Curt Swan & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: We just ran all the way down from 42nd street way up to 80th street and back. We were nuts. We were living. There are stories I can’t tell you.

Stroud: I’ll bet. I wanted to mention that I looked up your credits in the Grand Comic Book Database and you had over 3,000, for heaven’s sake. Does that surprise you at all?

ME: No, it doesn’t. (Chuckle.) I think I saw something like that in the end of my book, “Partners for Life,” they had a page of all my credits over the years and it was like 2 or 3 pages.

Stroud: It’s just amazing how much you’ve produced over the years.

ME: Well, you know you stay healthy and you churn it out. Ross and I did a lot of work and I did it with Johnny Romita and I did it with quite a few pencilers, plus penciled my own stuff years ago when I was a kid. Did you get a chance to find the book “Up Your Nose,” or “Get Lost?”

Stroud: I looked them up online and they look like great fun. I’m still planning to get a copy of “Get Lost.”

ME: “Get Lost” is a good book. It really is. “Get Lost” is the last thing I published, but actually the first thing I published with Ross in 1953.

Stroud: So that one has come full circle for you.

ME: Well, it really did because that book holds up so well over the years. It doesn’t look dated at all. At least I don’t think so. And the comedy is very well written. Ross and I, we laughed our heads off doing it and I think we did a good job.

Stroud: I’m sure you did. And as we discussed earlier if you hadn’t done a good job, Mad wouldn’t have taken an interest in calling you on the carpet for it.

ME: That’s right. They wanted to kick us right out. Well, they did in a sense because our distributor was canned by Mad and they distributed Mad as well and because of that we had no distributor.

Stroud: You’re dead in the water then.

ME: Right. And he was kicked out. He lost Mad as a comic book before they became a magazine. Then they went to National Periodicals. DC. To become a magazine. I’ll never forget Yvonne Ray, who did some writing for us, she was very good, and she used to pick up all the Twilight Zone type comedies. She’d make comedies out of them. These 5-page weird stories with crazy endings. It was based on the Twilight Zone type of theme. They were like mysteries with a little twist at the end. She put a couple of magazines out. She was the editor on one of them. Weird stuff.

Star-Spangled War Stories (1952) #101, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Anyway, she told me and Ross one day, “Why don’t you go to DC, National Periodicals?” Because we worked for them with the war stories. We were freelance cartoonists for them. For Bob Kanigher. And I was so embarrassed to even think of that. I said to Ross, “No, we’re not going to go there! After what we did to Mad.” And they were distributing Mad now as a magazine. But we were going to put out a magazine called “Get Lost,” like Mad’s magazine. And she said, “You should go back to DC.” And I said, “How can we face them?” We just couldn’t do it.

So, Ross and I said no. We tried to get our own distributor, which is what happened when we did “Up Your Nose” with Kable News. Anyway, I guess we should have gone (chuckle) to DC. You never know. The feeling was that, “Who the hell are we, two cartoonists for DC, doing frogmen stories or war stories, doing the Flash; we’re going to go in there and tell them we want to put out a book or a magazine for twenty-five cents they were in those days, for a black and white magazine like Mad called ‘Get Lost’.” Who knows? Maybe we would have been picked up right off the bat. Maybe they would have said, “Yeah, why not?”

Stroud: Yeah, you could have been ahead of your time.

ME: But it’s all under the bridge and into the water to even think about it now. What is that? You always think about what could have been. And if I had been born a woman, I would have been beautiful.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: I would have been. If you’re going to be silly, be really, really silly. Go all out.

Stroud: I like the way you think, Mike, I really do.

ME: Thinking about the movie that just went on, which I’m not going to watch because I have it on DVD, “Some Like it Hot.” It’s funny, this morning they had Joey Brown on TCM in an old movie, 1937, and he was so funny. And I was telling my wife, “You know, when I was a kid, movies, they say, don’t affect you. It does affect you.” What kids read, and what they see does affect you. Because I was an impressionable kid, and when I saw things like Joey Brown or films with a pretty blonde, and the guy keeps getting kicked around by the pretty blonde, it affected me. So, I never wanted to go out with a pretty blonde!

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: Was I stupid. But I was always feeling the embarrassment of the underdog. They were all underdogs, being taken advantage of by a sharp woman. When I was in the Army in 1945 in Tulsa, Oklahoma and this beautiful blonde was at the piano. It was a baby grand and there was a live orchestra playing soft music. She’s holding a cocktail and she sees me in my uniform. A young kid, 18 years old, probably attractive to her because she was probably in her mid-30’s, and she calls me over (chuckle) and I’ll never forget her words, she said, “Don’t be afraid. I’m not going to bite you.” I’ll never forget it. I was shaking in my boots. I was a kid. I was 18. And here was a worldly woman in a state that had no liquor! It was a speakeasy. There was no liquor in those days. Those were the dry states and dry cities.

Stroud: Mercy. What a great memory. You’re absolutely right, too, those things do stay with you.

Girls' Love Stories (1949) #141, cover penciled by Ric Estrada & inked by Mike Esposito.

ME: They stay and they affect you. A young girl across the way where I was standing with this woman had two soldiers my age with her, and they waved me over to their table. The girl was like 17 and I felt more comfortable and she became so friendly with me that she wrote me letters in Germany and she kept going and going sending me mail. No other girl I knew did. So, you meet people your own age and style and you feel more comfortable. Anyway, I do digress.

Stroud: Quite all right. I’m enjoying every minute. You inked after Ross for years and years. I know an inker’s got a pretty important responsibility, so was he tough to clean up after?

ME: Ross was a difficult guy to ink. First of all, he’d dig into the paper so much that if you had a pen or a brush the grooves would stop your line. He was really hard to ink. But good. His stuff was so beautiful when you looked at it, you wanted to ink it. But when you tried to ink it, it’s not easy. Some guys really know how to do it but rubbing the eraser over it and just making it disappear, guys like Frank Miller and stuff like that, they re-do the stuff to the point it’s not even him any more. But what Ross liked about me; he used to say to me, “I want it to look exactly the way I penciled it.” And that’s the way I was trained to do it with him. So, if a guy had a lantern jaw, that’s what he got. If Wonder Woman’s eyes were bugging out, that’s what he wanted. People used to think I was doing it. I said, “No, no, no. It’s in the pencils. It’s just that I follow his pencils.”

Stroud: And you were true to it.

ME: True to it and to the point I got criticism that I didn’t know how to ink Ross. Because it didn’t look good. But that’s the way he wanted it. Guys like Frank Miller and people like that would alter it to such a state that you didn’t see Ross, and they thought they were doing a great job.

Stroud: Sure, but that makes no sense to me. The original design was what was intended, obviously.

ME: Well anyway, we did well together and he appreciated what I did because I followed it. And then certain editors or other artists thought that all I was doing was doing what he did. Some inkers were so frustrated; they felt they had to make it look like their stuff. Well, I was trained by Ross to make it look like his stuff.

You get a guy like Tom Palmer, who is very good. Tom Palmer I always thought was a genius. I got him his first job up at Marvel. He was just a background man. When I saw his stuff when he was working for me a couple of times, I said, “You’re too good for this.” I called up Sol Brodsky up at Marvel comics and I said, “I’ve got a guy that shouldn’t be doing backgrounds. He should do features.”

So, I sent him to him and he got the job and he did some great stuff in the black and white magazines. The vampire stuff, you know? And he did a great job inking. The only guy I thought could ink Gene Colan the right way was Tom Palmer. Gene Colan used to pencil like a photograph. He’d use an outline of it. But he knew how to take that photograph look and make it unbelievably crisp. Whereas Frank Giacoia and I would ink him and we’d do it as an outline, because he didn’t work in lines. So, you’d destroy his soft pencil sketches by putting a hard outline. And the only guy that really knew how to do him was Tom Palmer. You look up the stuff and you’ll see how beautiful those black and white vampire books and Dracula books turned out.

Stroud: I’ll have to do that. I’ve heard similar things about Bernie Wrightson when he would ink his own stuff they said he was the only one that really should do it for some of those same reasons you were just talking about.

Weird Wonder Tales (1973) #6, cover penciled by Larry Lieber & inked by Mike Esposito.

ME: That’s right.

Stroud: That real light kind of a fade rather than a hard line.

ME: That’s exactly right. There are some guys like Frank Giacoia and myself, Johnny Romita, too, for that matter; we were trained in the school of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. Everything was line, line, line. It was all lines. It didn’t look like an illustration, where the line is secondary. And naturally all the colors take over when you make a painting. The outline is secondary. You never use black as an outline on a painting. You use colors. A brown against a green and it creates its own line. Well, Norman Rockwell.

Stroud: Yeah, a perfect example.

ME: Yeah, he never used a black line. He used tone, and some guys learned from a guy like Norman Rockwell, but we didn’t. We learned from comic books. We learned from comic strips. Our period. Terry and Pirates. Flash Gordon. Now there was a guy, Alex Raymond, who really could illustrate. He used to photograph everything besides when he did that Sunday strip when he left Flash Gordon. It was a detective type thing. Anyway, he used photographs, but he knew how to use those photographs and just put enough wispy line on it and have it reproduce with color on the comic strip. Another guy was Hal Foster.

Stroud: Prince Valiant.

ME: Right. These guys were really illustrators. Not cartoonists. And by cartoonists, I mean caricaturists of life. They wanted to draw real life.

Stroud: There is a difference.

ME: Right, but there’s a personality with a cartoonist that you can’t deny. They give it charm; they give it warmth, and personality. When you get a guy like Gil Kane, who can draw like crazy; he really can draw and his black and white stuff is beautiful on the syndicate strips he drew over the years. That special strip he had about science fiction.

Stroud: Oh, yeah, Starhawks I think it was.

ME: Right. Brilliant stuff. But it was too good for comics as we know it. Guys who really did the comics well, I think, are naturally Milton Caniff, which was the start of all that stuff; Johnny Romita, who was a Milton Caniff fan, to such a point that he almost had a chance to ghost for him when he got old.

Stroud: Holy cow.

ME: Johnny was young, and he had a chance to try out to be one of the ghosts because they had so many of these guys who had so much money, they didn’t do hardly anything any more.

Stroud: Sure. The Bob Kane school of production.

ME: Right. Anyway, Johnny Romita is brilliant with a pencil and a brush. It sings. It’s beautiful. It’s smooth and silky. Something Ross could never feel. He was not silky and smooth. But that didn’t mean he didn’t have drama. As I said there was a picture in one of the books that I have that reproduces Ross and me in the book, “Partners for Life;” a certain scene where he’s coming down the fire escape to the floor where the garbage pails are to the ground and in the alleyway, he goes on to the police cars. It’s like an “L,” the letter “L.” He comes down and goes down to the bottom and then goes forward, down to the background. That’s depth. That’s movement. And do you know where Ross got that? He got that from Disney’s “Bambi.”

Andru & Esposito: Partners For Life by Mike Esposito & Dan Dest.

Stroud: Really?

ME: Do you remember when the rabbits were running? The camera came down on them and I couldn’t believe it when I was a 14-year old kid watching it. It came down on them and it looks like it turned around to their rear end going the other way. Now, you don’t do that with a cartoon. Everything is flat and that’s it. But they had that pan camera, that special depth camera and they spent a fortune on one scene. I remember in Pinocchio with the little children running around in the streets from up above. They paid $40,000.00 for the multi-plane camera that Disney’s brother Roy said, “Stop! Stop! We can’t afford it!” So anyway, you want stuff like that, you pay through the nose.

Stroud: It turned the world on its ear. It was a good investment.

ME: Now we’ve got it all on DVD and we slow it down and look at it frame by frame and you’d be amazed what those guys did.

Stroud: It really is incredible what they were able to accomplish with the technology of the time.

ME: And that’s why they say nobody wants 2-dimensional drawings any more. They want the 3-D effect from the computer animation.

Stroud: Yeah, the Pixar’s and that kind of thing.

ME: Well, I’ll tell you. It is good. When you look at Monsters, Inc. with the one-eyed character voiced by Billy Crystal, it’s very good and very clever with the John Goodman character, Sully, the hairy blue monster. And then when you look at Bambi and you look at well-drawn animation like Pinocchio, the original Fantasia, you say, “My God. What went into that?” It’s really not 2-dimensional. It’s really not 3-dimensional. But it’s rounded. It looks real. And the kid’s shows all have it now. And it does improve the quality for a little kid to look at and it looks like it’s really coming to life. Anyway, we went into another direction.

Stroud: (Laughter.) I don’t mind. When you were inking other pencilers besides Ross was there anyone you really didn’t like inking?

ME: No. Some of these guys were so good. Johnny Romita, I loved inking. I don’t know if I did him justice; the way he wanted it himself when he would ink it, but I loved inking his stuff because it was all there. Silky, silky clean. Then there was John Buscema. Excellent. Especially when he did full pencils. But then he got annoyed when he realized he wasn’t making enough money like his brother, Sal Buscema, who was turning out five pages a day in breakdowns and blue pencil. And he was very careful with what he was doing and then it was, “What am I, nuts? I can only do one page a day. My brother is knocking out five pages a day.”

Stroud: This isn’t cutting it.

ME: And Mike Sekowsky used to turn out five pages a day. And good. Really good.

Stroud: I’ve heard Mike was just amazing.

ME: He was a machine.

Inferior Five (1967) #1, cover penciled by Mike Sekowsky & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: Joe Giella called him “The speed merchant.”

ME: You got that right. Joe Giella did a lot of work with him. I did a lot of work with him, but not as much as Joe because Joe was with DC all the time. I did some humor stuff with him of course, which you know about, the Inferior Five and whatever.

Stroud: Yeah. It seemed like a fun series. It’s a shame it didn’t go longer.

ME: Well, this is what happens, unfortunately. They put the books out for three months, give it three issues, and if it doesn’t grab hold, they go to another three issues of another title. That was Bob Kanigher’s job, and all the editors. They’d come out with a new book on the title of Showcase. They had to have a new idea, and Bob’s turn was coming up for an idea and he had no idea. He was strictly a guy who loved to watch movies. We’re talking 1955 science fiction. So, he came up with the idea of robots.

Stroud: The Metal Men.

ME: He called up Ross and me and said, “I’ve got to have something within a week.” Ross said, “What are you talking about?” Ross was slow to begin with, and we had to come up with something. Then we came up with the Metal Men design. We designed it for him. He flipped out. He loved it. And I’ll tell you something. It was good. Metal Men was a good book.

Stroud: It’s one of my all-time favorites.

ME: Well, I’m glad to hear that. There was a lot of personality in there. I used to say to Bob, “Bob, you know what you got here? You’ve got a newspaper strip. Every day, showing the personalities of these guys. Or maybe a T.V. show.” But you couldn’t do the T.V. show because they didn’t have any computer-generated effects. He said, “Nah, you don’t know what you’re talking about.” He belittled it. Anybody who had an idea, he would override it. “Just do your inking. You’re not being paid to think.” I used to hate that expression: “You’re not being paid to think.” I’d come up with an idea now and then because I was creative. I had ideas and I would bean him with them. “You’re not being paid to think, Mike.” Anyway, that book was classic for its time.

Stroud: Very much so.

ME: Bob didn’t really believe in it in the beginning. Then he couldn’t believe it because Ross and I put our guts into it. We flew through twelve issues.

Stroud: Yeah, in fact I ran across a statement that will probably ring true to you. It said, “Kanigher performed a similar astounding delivery when he created and scripted a superhero classic, the Metal Men, for Showcase #37, March/April of 1962. He art directed his artists, Andru and Esposito on the layout and they heroically rendered the story, completing the book in only 10 days, cover to cover.”

ME: That’s it. That’s it. I don’t know how the hell we did it.

Stroud: I don’t either. That’s astounding. I was going to ask you if you remembered it. Did you just not sleep? (Chuckle.)

ME: Oh, we didn’t. We’d work 45 hours. (Chuckle.) When you look at “Get Lost,” if you get a hold of a copy, and you see the picture of Ross and me holding up “Get Lost,” look at Ross’ eyes. He looks like a vampire. Like shot, he’s shot. You look at me and I look 30 pounds heavier, because all I did was eat! It was to keep from sleeping.

Showcase (1956) #37, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: Some way to keep going. Oh, my goodness.

ME: And I’m telling you, that’s very true what he said in that book. But at one point he wrote somewhere giving Ross and I credit for co-creating it with him, which was nice. This was years later. Some of the reprints that were put out years later said, “Co-created by Andru and Esposito.”

Stroud: That’s almost unheard of. A lot of people like Mort Weisinger, for example…

ME: Oh, poor guy.

Stroud: He wouldn’t give credit to anybody.

ME: No way! (Chuckle.) He used to run through the hall. This big, heavy guy and he’d be on his toes. Ti-ti-ti-ti-ti-ti. Running around like a little pixie.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: You’d look at him and he was so light on his feet. A story about him: I feared him so much. Because he would take the pages…I was doing Wonder Woman then, too, along with the Metal Men. Trying to squeeze Wonder Woman in every month as well as Metal Men those first 10 days.

Stroud: Oh, goodness.

ME: And it showed. It was kind of raw at times, because we were burned out. But he took the pages one day, and he was looking at them, and I happened to have them on the floor. “What have you got on the floor there? You got $2,000.00 on the floor! What if they get dirty? What if somebody steps on them?” I said, “It won’t reproduce the dirt!” He was annoyed that I was too smart. I mean I’d published. I knew all about that. It can’t reproduce, you dumb ox. The grease from ketchup and stuff like that, when Ross and I would be eating and Ross was sloppy with his eating, his hands were always dirty from food and his pages were dirty from grease marks and what have you, but when it’s printed, it’s clear as a bell! You don’t see that. And he [Weisinger] got annoyed. And he was kind of hard on me sometimes.

Stroud: You and everybody else it sounds like.

ME: Yeah, he was a pretty tough guy. And I was going to buy a house with my late wife at the time, in Dix Hills, which was a very nice neighborhood. It was a ranch house. This was about 1962 or ’63, and I went with the salesman and he showed us the house. Beautiful house. He said, “What do you do?” I said, “I’m a cartoonist.” “Well that’s good. We have cartoonists out here.” I said, “Who?” “Mort Weisinger just bought the house next door.” I said, “What? Mort Weisinger? Forget it, let’s go.”

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: I walked away from the house. I said, “I’ll be damned if I’m going to live next door to Mort Weisinger.” The first thing I’ll hear is, “You’re making too much money if you’re living out there with me.” That could happen, you know.

Stroud: I believe it. And who would need that? I think I read an interview somewhere with Arnold Drake and he referred to him as “The Whale.”

ME: That’s right. That’s very good from Arnold Drake. Arnold Drake the writer?

Stroud: Yes. I don’t know if you remember or not, but if I recall there were actually four appearances by the Metal Men in Showcase before they got their own book…

ME: At least three.

Robin Hood Tales (1956) #10, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Astonishing Tales (1970) #21, cover penciled by Gil Kane & inked by Mike Esposito.

Showcase (1956) #71, cover penciled by Mike Sekowsky & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: In one of them at the end it said, “Readers, you let us know if you want to see more of us,” and then in the next issue of Showcase they were back again. Do you know what happened there?

ME: No, I don’t know. I do know that we did three issues, and the first cover I hated. Because the figures were little tiny figures of the Metal Men near the bottom with this big Stingray coming down. The Stingray was the whole thing. Bob Kanigher was into science fiction with the movies and the Stingray was the big flying thing in the first Metal Men. That was timely for that time because of all those cheap 50’s era science fiction movies, with “The Thing From Outer Space,” and all that stuff. Ray Harryhausen stuff. Some of them were good. I enjoy looking at them today, but he would borrow from almost every one of those stories. They weren’t Bob Kanigher’s creations. He saw the movies and recreated and rearranged the thoughts into a comic book.

Stroud: Ta-da and there you go.

ME: He had a very fertile brain and he knew how to do that. Not only that one; he did it for almost all of his books. A lot of the science fiction stuff that he wrote was borrowed from science fiction movies; which was understandable, because people did it all the time. There was only one original and then you filter it many directions.

Stroud: No new ideas.

ME: Well, I always use the expression like people say, “Getting to the top,” and I said, “Look at a pyramid. There’s only one on top and a billion slaves underneath.”

Stroud: Good analogy.

ME: There’s only one on top. It’s so difficult to be a winner. So difficult. With a syndicated strip, with anything. Number one this or number one anything. So difficult, but you can be popular and you can make money, but you’ll always be near the middle somewhere. You’re probably not going to get to the top. People who got to the top…what’s his name with Playboy?

Justice League of America (1960) #71, cover penciled by Mike Sekowsky & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: Hefner?

ME: Hefner. Now I saw him crying the blues in the reception office of National Periodicals, which is DC’s company. It was called National Periodicals. And he was walking back and forth with a little magazine under his arm. Back and forth, back and forth. I’m sitting in this chair, because I was waiting for Ross. We were going to go in there and pitch some of our ideas to DC after we were freelancing there, but not “Get Lost,” we were going to do other things. And I found out who he was. He had the first book with Marilyn Monroe on the cover. Playboy. And they bought it. National Periodicals decided to print and distribute it. And he rocketed to the moon. It happens. Gaines had the chance, but he was a bastard and who the hell knows? He could have gone further, but he had some good help. Gaines had a lot of good people working on Mad. Mort Drucker. A lot of good, famous artists.

Stroud: Yeah, Al Jaffee. Lots of good folks. Russ Heath was there for awhile.

ME: Russ never had a sense of humor with his artwork. He was more graphic and detailed. He was good. Not so much in Mad magazine, but his adventure comics were terrific.

Stroud: Right, the war comics and westerns and so forth.

ME: Russ Heath always impressed me because I knew him when he was very young and starting. He was very impressive with his knowledge of horses. For some reason I’m thinking he was brought up out west. But horses, he loved horses. And he was very detailed.

Stroud: His work is quite impressive.

ME: Very much so. But he doesn’t have a sense of humor in his work. That’s not a fault, it’s just that you could never give him something like a Mad magazine gag situation and make it funny. He’s not the type. I guess that’s where Ross was different and I guess myself, too. We could do both. We could be very serious, very dramatic, and very funny. Not every partnership can do that. Not any one inker can usually do that. Not any one penciler can do that. But Ross and I seemed to excel in both areas.

Stroud: That’s a gift.

ME: It’s a sense of humor that you retain through all the garbage.

Stroud: It keeps you going.

ME: Right. Ross and I were very funny when we’d be writing things until 3 o’clock in the morning, and we’d make up things as we went along and we’d start to play act. That’s what we did. Anyway, it was a great ride.

2006 Wonder Woman postage stamp. Art by Andru & Esposito.

Stroud: Were you surprised when your Wonder Woman was made into a postage stamp a couple of years ago?

ME: Oh, definitely. I got a nice check from DC. A big check. I couldn’t believe it. But they wanted me to go out west to sign stuff in San Diego, and I said, “No, I don’t want to.” I said, “I don’t leave the house.” They didn’t bother me any more. They accepted the fact that I wouldn’t go, but they didn’t say, “Give me back the check.”

Stroud: (Laughter.) You know that’s one thing that some of the folks I’ve had a chance to talk to have told me. It seems like the consistent story is that DC’s been doing a good job of paying royalties to the talent.

ME: You’ve got that right.

Stroud: But Marvel has kind of fallen behind.

ME: It has. I was talking to my wife about having to pay $600.00 for the damned oil. It’s going to get cold soon, and I’m waiting for a check from Marvel because they put out a lot of books recently where I did almost all of them. Like the Iron Man book from the movie. I’ve got tons of stuff in there. It’s probably a couple of thousand dollars if I get it. I’ll get a little check from them, but never the big checks. So maybe they’ve slowed down, but why I don’t know. They made a fortune on Iron Man.

Stroud: Exactly.

ME: They own every penny. They produced and directed it and own it. It’s not like before with licensing where they got 5%. They got it all. The DVD’s. It’s all theirs.

Stroud: Yeah, in house production and everything.

ME: Right. You’re going to see a lot coming up, too. They’re gonna come out with Thor. They picked Thor because it’s different from the regular superheroes. It’s going to catch on with regular audiences that are not fans of comics only. It’s very mythological.

Stroud: Right. It would have a broader base.

Iron Man (1968) #1, cover penciled by Gene Colan & inked by Mike Esposito.

ME: Right, and I think it will make a lot of money. I don’t know who’s going to be in it.

Stroud: I’m not sure either, but that’s a good point. I hadn’t thought about the fact that it would appeal beyond the comic book fans.

ME: That’s exactly right. And of course, DC made $500 million already with Batman.

Stroud: Oh, yeah. The Dark Knight is going through the roof.

ME: Right, and they sent me a little check this morning. DC, like you said, is very quick to pay, along with balance sheets and everything to double check when I was paid this or when I did this or when I did that.

Stroud: Yeah, I’m sure you’ve seen the Showcase Presents reprint collections they’re doing now. They’ve been real good.

ME: Which ones?

Stroud: They’re doing particularly Silver Age stuff. They’re doing Flash, Green Lantern, Atom, Justice League…

ME: Well how long ago are you saying?

Stroud: Just within the last few years.

ME: Oh, okay.

Stroud: They’re a black and white paperback.

ME: Yeah, I’ve been paid and get my residuals on those. About a year ago.

Stroud: I think on the Metal Men they’re getting ready to release Volume Two.

ME: Really? They haven’t done it yet?

Stroud: If I’m not mistaken.

ME: Well, they put a Metal Men out about a year ago.

Stroud: I wonder if that was the hardbound color Archive Editions?

ME: It was about a year ago and it was Part One. It was not the whole ten years. So, there should be another one. I’m hoping, anyway.

Stroud: I’m sure there will. They had a real following. They did very well for a long, long time.

ME: Metal Men?

Stroud: Yes.

ME: Good. I’m glad you said that. I know they sent me a set of all the Metal Men figures two years ago.

Amazing Spider-Man (1963) #41, cover penciled by John Romita & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: How nice.

ME: They sent me a whole box. I was surprised. They were a very good-looking job they did.

Stroud: That’s neat.

ME: I used to get orders from fans who would want a Metal Men cover or a Metal Men head. Stuff like that.

Stroud: Are you still doing commissions, Mike?

ME: Yeah, I am, but I don’t have the energy to turn them out like I used to. I’m 81 now. I have some finished work on hand, like #40 of Spider-Man standing over the Green Goblin. The famous one you see all the time. I’ve got one lying on my table. Maybe someday someone will buy it. And I’ve got about 4 or 5 others that are 90% done. They’re just sitting there. I have no way of distributing it.

Stroud: (Chuckle.) Back to the distribution problem. When I talked with Carmine [Infantino], he praised your and Ross’ artwork to the rooftops on the Flash…

ME: I’m glad to hear that. I really am.

Stroud: He said it was wonderful on the Flash and he was surprised that some of the fans were unhappy initially.

ME: That’s right. They were.

Stroud: I guess it was just the notion of a change.

ME: They were. First of all, Ross, when he drew the Flash, compared to Carmine; Carmine made him two dimensional. Lean, very lean. Always running with the same arm out and leg back, you know? And he was swift! Lithe and swift. But when Ross did it, he made him muscle bound. Because Ross, being part Russian, he used his legs. Now my legs are skinny, like Carmine’s. (Chuckle.) Ross used to look at me in the mirror at the hotels and so on, and he’d say, “You got no legs. You call those legs? These are legs!” Boom! Boom! Big, muscle bound legs. That’s the way he was built. He was Slavic. And I was a slob.

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: Sorry about that, but the humor never stops.

Stroud: I appreciate it. I sure do.

ME: You can write a book now. Anyway, he drew himself. And that’s what bothered the people. He didn’t look swift any more. But then when the movie came out, the T.V. show, it looked like Ross’. Remember the T.V. show during the short time that it was running?

Stroud: I sure do.

ME: And it had the thickness of what Ross was doing. Now, they didn’t want to use a skinny guy flying around, they wanted to use a muscular guy. He was a guy who was going to punch guys out. And in a sense Ross was right. But the fans, they would never say die. The king is dead. Long live the king no more. Because Carmine was the king of what he was doing, and we come in, upstarts, you know. “What did you do to Carmine’s Flash?” And they weren’t happy. When they had letters to the editor in the book, they tore us apart.

The Flash (1959) #175, cover penciled by Carmine Infantino & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: Some of them were pretty brutal.

ME: They were. But you said Carmine appreciated it.

Stroud: He did. When I spoke to him I told him, I said, “After you left the book, it seemed like poor Ross and Mike couldn’t get a break,” and he says, “Why? They did wonderful work. Why were they (the fans) that way?” So, he obviously appreciated the work that you guys did.

ME: Well, visually, in the content with Ross, his depth perception was evident in the book when it never was when Carmine did it. Carmine would have the guy running with buildings in the background. Skyscrapers. Ross didn’t do that. He went in and in and in, like Disney’s multi-plane effects and that’s what Ross and I grew up on. Multi-plane. In, in, in, in. There’s a front, there’s a center plane, the middle plane and the background. Way in. And when you draw the guy in the background, then the multi-plane should be way up the front plane so you get depth.

Stroud: It makes perfect sense.

ME: Yeah, but a lot of guys don’t want to think that way.

Stroud: Too much work, I guess.

ME: Well, not only that, but not as attractive. When Ross did it, the young readers of Ross’ stuff never appreciated that plane. That depth. They liked Gil Kane’s, which was visually beautiful to look at the figure, with a wall behind it. You follow me?

Stroud: Yes.

ME: There was no depth. No planes. One guy that came close I would say would be John Buscema. John Buscema had great style. I remember the book I did with him on the Avengers. It was the wedding of the giant girl. I loved that story. He drew her in a gown, and I think the giant girl was marrying the little guy. What was his name? The ant? Not the ant.

Stroud: I thought maybe you were talking about Ant-Man, but I’m not sure. I don’t know my Marvel characters as well.

ME: I don’t think so. Whatever it was, she was marrying the little guy, and the way he drew that gown was unbelievable. When I inked that, I had never been able to ink Ross this way. It just flowed off my pen. So, to me, he did things Ross couldn’t do, and I did some Thor books with him, too. A couple of books. I did so much inking my fingers were full.

The Flash (1959) #187, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: Sure. I saw where you even inked Steve Ditko there for a little while.

ME: Yes, and I got in trouble because he did the last issue of U.S. One or whatever it was that was written by Al Milgrom, and the penciler was Frank Springer. Beautiful stuff. Really beautiful. I had so much fun doing it, because he was an advertising artist. He knew how to draw trucks. The trucks for U.S. One and the characters were so good, I loved doing it.

And then the last story had to be done and Milgrom said that Springer wasn’t going to do it, so they got Ditko. And I couldn’t make heads or tails of it. So, I went to the editor, whose name was Ralph Macchio, and I went up to him and I said, “I can’t do this.” Well, he got really pissed off. He got mad. And actually, he’s the boss and I’m only the worker, so turning down a job, and he wanted it finished because it was like the 12th issue, the final run of the book, well, that was unacceptable. I told him, “I can’t do it. It’s all scribble. It’s not the style that was there before. I’ve got to try and make it look consistent.” Springer was the guy who should have finished it, but Springer was put on something else. So, I refused, and ever since then he never treated me well. He didn’t give me work. If he did give me work it was the worst jobs. The worst characters.

Stroud: How dirty.

ME: One you wouldn’t make money on in reprints. That idea. Things like Iron Fist. I hated that character. I mean there are some losers up at Marvel, believe it or not. They did like 40 different characters a month for the Marvel Universe. Some were great, but some of them were…what it was, was they had all these young writers. They were creating things off the top of their head like crazy, and they were accepted because they had to turn out 40 books a month.

Stroud: So just give me product, huh?

ME: Right. And it showed.

Stroud: Yeah, when you’re mass producing like that your quality is probably not going to be able to hang in there.

ME: And when you’ve got a guy like Roy Thomas, a damn good editor, he had enough to handle, he almost had a nervous breakdown because of all the work they had to turn out. Johnny [Romita] was going nuts because he had all those covers to do. That’s when they brought in Gil Kane to do the covers with Johnny. And Johnny Romita used to get so upset with Stan Lee and say, “We’re doing too many books!” And Stan Lee would say, “You’ll never be number one, Johnny. You don’t think like a publisher who wants to be number one. We want to be number one. We have to have more books than DC.” And he was right. Stan had a vision, and he was right. Stan was a bit of a genius. You know the story about him standing on the table and telling me how to draw?

Stroud: Was that the Green Goblin?

ME: No. I was penciling then. Sol Brodsky was there by the table, and he was telling me something I was doing wrong with the criminals. He said, “No, you’ve got to give them a thick neck, you know? Big, knobby hands.” And I was drawing my own hand, which is delicate. I’m not a knuckle-bound, thuggy guy. And he said, “No, you’ve got it all wrong. He looks like a lawyer. You’ve got to make him look like a thug.” And he gets up on the top of the table and he starts acting it out, showing his thick neck and all that and Sol Brodsky is standing off to the left starting to laugh. Some guy called me up in February. He’s writing a book, an interview with me about that scene. It will be appearing in one of these TwoMorrows type books, I guess, about Stan Lee and so on. You’ll probably see it when it comes out.

Not Brand Echh (1967) #1, cover penciled by Jack Kirby & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: I’ll have to be on the lookout. I’d heard the story, but I didn’t realize that it was with you.

ME: Yeah, he did it with me. He did it with a lot of guys. In my take, it’s Stan Lee and a little picture of me.

Stroud: Super. Was that in your Mickey Demeo days or was that later?

ME: That was Mickey Demeo days.

Stroud: Demeo, I’m sorry. (Note: I mispronounced the last name.)

ME: No, don’t be sorry. I should be sorry.

Stroud: (Chuckle.)

ME: Because others knew it all the time, but never once called me Mickey Demeo. I was hiding behind a name. Because at the time I was doing work for DC under contract with Wonder Woman and all that stuff. The satire stuff with Mike Sekowsky. So, when Stan said to me, “I want you to work here on staff,” I said, “Well, I can’t.” He said, “Well, use a pen name. Everybody does.” Gil Kane was somebody else. The only guy that didn’t change his name was Johnny Romita because he had no other company he was working for that he would get in trouble.

Stroud: No need to hide, huh?

ME: Right. But everybody else did. Even Jack Abel had a different name. They all had different names. So, Stan said, “Go ahead and change your name.” So, I said, “Mickey Demeo.” He said, “I like that.” (Chuckle.) Then he gets a letter...this is the truth, the God’s honest truth, he gets a letter from a kid in England, a big fan; wrote him a letter that said, “You know, Mr. Stan Lee, I know who Mickey Demeo is. He’s Mike Esposito. I can tell by the way he does the ears.”

Stroud: (Laughter.)

ME: Stan is telling me this and I’m laughing my head off. I said, “You mean to tell me that’s what it is?” They see things that you don’t realize they see. The way you do fingers, or hands. The way I did my ears. You can’t mask that. It’s an ear. The kid was sharp. I’d like to find him now, the dope. This must have been around 1961 or ’63. Something like that. The kid was sharp.

Stroud: That’s an eye for detail.

ME: That’s right. And Stan was saying that, “You can’t fool the young readers. The fans know everything.” He was right. That’s why he was the only guy…DC never did this, the only guy that would make sure that every artist, writer, letterer, was signed with little nicknames.

Chamber of Chills (1972) #7, cover penciled by Ron Wilson & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: Right. You were “Mighty Mike” as I recall.

ME: “Mighty Mike” Esposito, “Jazzy” John Romita; everyone had a little nickname, and the reason for it is that he was copying Hollywood. He was thinking in terms of character actors so that people would remember them. You’d associate the name to what he did.

Stroud: Of course.

ME: Otherwise it’s cold and cut and dried. You’d go up to DC and it was no name. Just the little numbers on the bottom of what story it was. 603452 or whatever.

Stroud: Yeah, although I did notice at least on occasion…

ME: Bob Kane.

Stroud: Well, yeah, good old Bob. (Laughter.)

ME: He made sure. What did you notice on occasion?

Stroud: That on the covers that you and Ross did…

ME: That was later, when we got a byline.

Stroud: Yeah, there would be a little square there that said, “Andru and Esposito.”

ME: Right. That was the Metal Men.

Stroud: Right, that’s what I was thinking of.

ME: It was years later with Wonder Woman because the creator of Wonder Woman was still alive. The guy was a writer and the name Charlie Moulton was on every Wonder Woman book. Every book had Charlie Moulton, so we could never sign it. And then finally… (dramatic lowering of voice) he passed away. It was our day.

Stroud: (Chuckle.) And you were able to take it from there.

ME: “Art by Andru and Esposito.” That was something good about DC. They would always say “Art by,” not “inked by” or “penciled by.” They saw it as an art team. “Art by Mike Esposito and Ross Andru.” I always felt good about that. Because it made me not look like what Marvel was doing. Some of those young editors would say, “Delineated by Esposito.” What the hell is delineated?

Stroud: (Laughter.) Yeah, talk about talking over the head of your audience. I notice you had some credits for doing the Hostess ads for awhile. How was that?

ME: I know I penciled a couple of them. It was nice money. I was up at Marvel and Marvel’s rates were low at the time, but these things paid like $100.00 or $125.00, so it was a big difference when you’re used to getting $25.00 or $30.00. But those jobs didn’t come often.

Stroud: Did you have a preference between DC and Marvel?

World's Finest Comics (1941) #177, cover penciled by Ross Andru & inked by Mike Esposito.

ME: As an inker?

Stroud: Right, just in general.

ME: I liked DC, because with DC I could use a lot of pen as opposed to brush up at Marvel. I was never a brush man. Johnny Romita wanted everything in brush, and I don’t blame him because the reason for that is that the color reproduction was so bad up at Marvel at the time, in the early days, it would bleed. In other words, you would have an outline on Spider-Man, and if the line wasn’t thick enough, with a brush, it wouldn’t hold the shape together. All the colors would be running into each other with the bad color reproduction. If you look at the old books you’ll see it. They’d overlap sometimes and run into each other.

Stroud: Stan Goldberg told me it was kind of a nightmare being a colorist back then.

ME: Sure. Of course, it would be. And he was a damn good colorist. One of the best. Not like DC’s colorists. Frank Giacoia and I went one day up to a meeting and he was really bitching. Frank was a funny guy. He was late on everything, but he made them know he was mad. So, they wouldn’t remember he was late. That was his whole game. He’d get annoyed. Then he’d look the other way and apologize. When you walk out with your check, even though you were late on the previous one, and they won’t even remember.

But what happened was we were sitting there and they were talking about the colorists, and the books. I think Jerry Serpe was the guy’s name. He was a colorist along with Jack Adler. He used to take his brush, and he’d put it in blue, and he started hitting everything with blue on the page. On the page they used to make the coloring. Not the original, of course. So, Frank Giacoia said, “You know, when you do that, you got blue mountains, a blue horse, you got blue grass. Wherever you put the brush and use it. There are other colors to use, too.” That’s how they’d knock out five pages an hour at $3.00 a page. So anyway, he got really mad and he stood up and I never saw Frank yell so much. And he got his point across. Because all of a sudden…I think Carmine was just coming into the picture as the top dog, and I think he listened, which was good. Because it was pretty bad. Those guys made so much money as colorists. We cartoonists were in the poor house by comparison. We’d do one page a day if we were lucky. They would do 10 pages in an hour to color.

Stroud: Wow.

ME: I’m serious. The colorists would use these little Xerox sheets and then those things were sold later for a lot of money. But when they colored them, they didn’t color them in detail and make sure no notes were off the line. Then they’d write “YR,” a certain type of yellow, “BL,” a certain type of blue, and they’d put the code numbers on it to make sure that the colorists, when they did it, the engravers, when they did the coloring, would use that code to make sure if they were off a little bit on the color, the code would tell them which one to use. They didn’t do any creative coloring at all. All they had to do was write down the code.

Stroud: Just follow the script, huh?

ME: Right. And they made so much money. They made over $100,000.00 a year then. Tons of money. They’d get $4.00 a page to color and they’d color tons and tons and tons of pages. The covers always got more. The cover would be maybe $50.00. A lot of covers. And I think that’s how Stan Goldberg got into it. He realized the coloring was very, very lucrative. And then you’ve got Marvel cranking out 40 books a month, and he did a good job. An excellent job. And he does a great Archie.

Defenders (1972) #7, cover penciled by John Romita & inked by Mike Esposito.

Stroud: He sure does.

ME: Without him, Archie would be dead. He really kept it modern and up to date. Michael Silberkleit up at Archie should kiss his feet every time he sees him. Because they’re not paying any reprint money. They just take the money and run. “Here’s your check. Goodbye.” Maybe he gets a little bit, because he did tons and tons of stuff with the digest books. Maybe he gets a buck a book or something.

Stroud: Speaking of Archie comics you were art director there for awhile. Did you enjoy that?

ME: That’s where I was doing the book called “Zen.” What happened was I met this guy, Steve Stern. He came from Maine and he created “Zen, the Intergalactic,” and he wanted me and Ross to pencil and ink it. Actually, we did some writing, too. We did about three issues. First, we did them in black and white and they were terrible. But finally, he got a contract with Archie to them up there, because Archie was looking for another “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” When that one came out of the blue it made them wealthy. So, they figured, “Hey, let’s try this ‘Zen the Intergalactic.’”

So, we did three issues in color and I was the art director and editor. So, it was pencils and inks by Andru and Esposito, created by Steve Stern, and colored by Barry Grossman. And we had a budget. Because we had a nice budget I told the colorist he could have $10.00 a page. Which was unheard of at Archie. It was the Japanese guy. Yoshida. And I liked that guy. And he was so happy because he’d never seen that kind of money from them. He’d get $3.00 to $5.00 tops. He did a good job. He did the lettering and Barry, for the coloring he got $10.00. And then after the third book they said, “It’s costing us too much money.” Before the results came in. “It’s costing too much money to put it out. You’ve got to cut the amount of money.” This is Michael Silberkleit telling me this. So, what could I do? So I had to cut it in half. I cut it to $5.00 a page, which hurt Yoshida. He was really upset. He said, “What happened?” I said, “I had to. They told me I can’t do it.” And I cut my rate. It was down to practically nothing left for Ross and me.

Stroud: Oh, man.

ME: This is what happens. And of course, they killed the book. After a few issues they discovered it wasn’t another Ninja Turtles that made a fortune for them. It happens. Lightning doesn’t strike twice.

Stroud: Well, it is a business, and that’s what it ends up being, first and foremost.

ME: Right.

Stroud: One of the things that I always thought was very unique about the work that you and Ross did was that bursting out of the panels look, when the figures went beyond the panel boundaries. Was that Ross’ idea or yours or collaboration?

World's Finest Comics (1941) #184, cover penciled by Curt Swan & inked by Mike Esposito.

ME: It might have been both of us when we did it for “Get Lost.” We had a scene where the kid was being beaten up and he’s falling through the panel and stuff like that, but later on, when he was designing the pages for DC or Marvel, that was his department. I didn’t sit down with him and discuss how he was going to do the penciling of a story that was given to him by Stan Lee for Spider-Man or stuff like that. He was on his own, and I was just the inker and he was the penciler. We had nothing to do with collaboration between us. When we worked for DC in the old days, with Metal Men and before we went to Marvel, when we were a pencil/inker team, then we had more time that we collaborated.

Stroud: I was thinking of this one particular Superman story I have that you both worked on and that technique was used a lot. One scene showed him visiting Lori Lemaris, the mermaid and it showed her being tangled up with this monster underwater and it completely broke out of the panel boundaries and I thought, “Gosh, what a neat idea.”

ME: Was that in Action Comics? We didn’t do many in the Superman book.

Stroud: I’m not certain.

ME: I remember one in Action that had his face poisoned by Kryptonite.

Stroud: Yeah, I’ve got that one, too, where he’s all green and disheveled. Anyway, I thought that was an extremely unique thing and I don’t remember anyone else doing it at the time.

ME: It was really Ross, I would have to say, when it came to designing pages as a penciler, but when it was the satire stuff, done in a humorous way, then I would incorporate my thinking more. I would be more involved with him in designing the pages.

Stroud: What sort of equipment did you use in your work?

ME: Well I used crow quills and I used more stiff points. Frank Giacoia schooled me in that area for pen points. Esterbrook, I believe it was called. I don’t think they’re around any more. A lot of those things disappeared - like Guillot, who made pen points. They had one with the little lip on the end that worked like a brush. You could almost bend it like a brush. And of course, brushes. The #3, the #2. I loved to do pen with the ink rather than the brush. Marvel wanted more brush. I still say it was because printing was so bad. They wanted a thicker line to hold the color what with the bad printing in the comic books in those days. It kept it from bleeding. With DC, they liked the idea of more pen work back in the old days. The 50’s.

Stroud: So that was your preferred tool rather than a brush.

ME: Well, it was good because I could draw on top with my pen like it was penciling on top of Ross. I used stiff points. Hard points. Not flexible ones. Then I could control it like a pencil. You’d get the clean lines, where a brush sometimes would get heavy handed, and you can destroy some of the guy’s contours. Like Jim Mooney used a very heavy brush, and when he would do Ross, sometimes he would change some of the hard contour approach. Stan Lee loved it because it was a thick line. You follow me?

Stroud: Yes.

ME: They liked the heavy line better. And Stan wasn’t wild about my using a pen, but that’s the way I liked to work. You could control it more like a pencil.

Marvel Team-Up (1972) #137, cover penciled by Ron Frenz & inked by Mike Esposito.

Swing With Scooter (1966) #10, cover penciled by Joe Orlando & inked by Mike Esposito.

X-Men (1963) #53, cover penciled by Barry Windsor-Smith & inked by Mike Esposito.